Circle Four Farms sprawls across 90 square miles of land in southwestern Utah. There are about 600,000 hogs here at a time, packed by the thousands into long warehouse sheds. About one million hogs—185 times the human population of the county—are raised at Circle Four each year, making it the largest factory farm in the state; its parent company, Smithfield Foods, is one of the largest in the world.

Circle Four Farms sprawls across 90 square miles of land in southwestern Utah. There are about 600,000 hogs here at a time, packed by the thousands into long warehouse sheds. About one million hogs—185 times the human population of the county—are raised at Circle Four each year, making it the largest factory farm in the state; its parent company, Smithfield Foods, is one of the largest in the world.

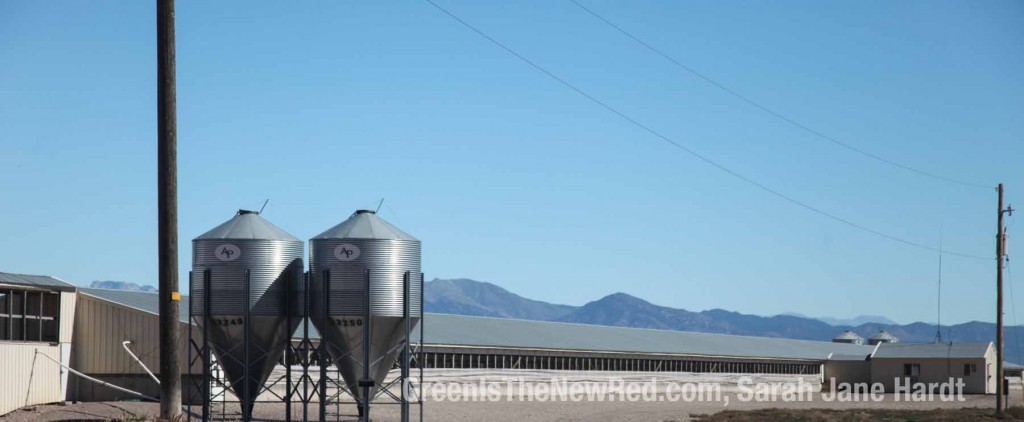

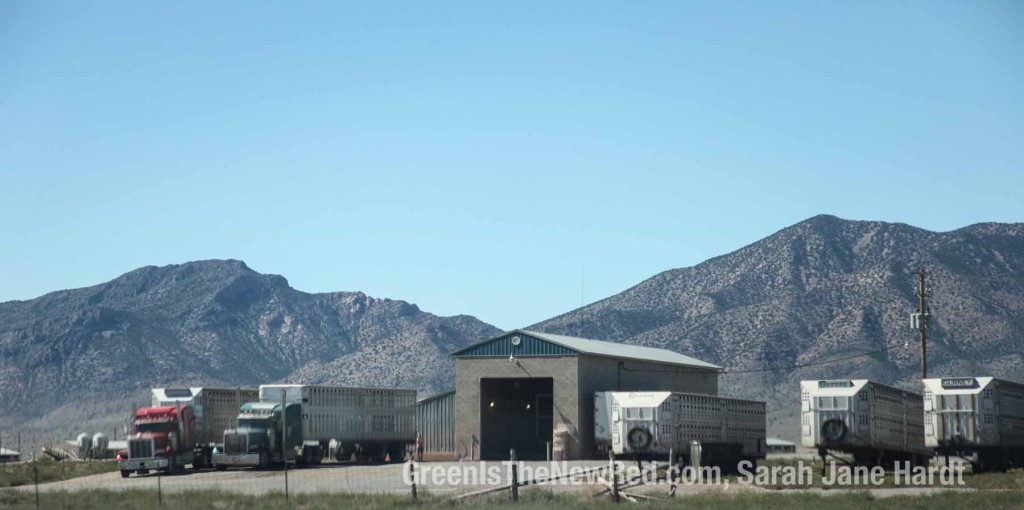

The farm is so large that its scale is difficult to view from the public road. At best, one could see a few of the sheds, some feed bins, trucks.

But Circle Four Farms has plenty of reasons to be wary of exposure, even from a distance. The company came under scrutiny earlier this month by the USDA because of a deadly pig virus. Last year, it was part of a controversial financial deal—the largest-ever Chinese takeover of a U.S. company. Public health studies have shown that people who live near the farm are much more likely to be hospitalized, for a wide-range of illnesses. And the farm has also been investigated by the Justice Department as part of the largest-ever case of human trafficking.

So it is perhaps not surprising that when farm employees saw people driving by on Wednesday, September 24th, and taking photographs, they reacted quickly. They followed the two cars, stopped them, demanded that they turn over their photos and, when they refused, called the sheriff.

Four animal rights activists had driven to Circle Four Farms on Wednesday, September 24th, to wait for slaughterthouse-bound trucks leaving the facility. They were going to photograph and videotape the transport for a national non-profit group called the Farm Animal Rights Movement. The photography was part of a series of efforts by FARM leading up to World Day for Farmed Animals on October 2nd.

When they were waiting for the trucks, one of the activists, Sarah Jane Hardt, photographed the farm from the street. The photographs, included here, capture the rows of sheds and the barren landscape, but not much detail of the farm.

much detail of the farm.

When they set off down the road again, that’s when Circle Four Farms trucks pulled in front of them and stopped them.

The workers repeatedly asked to see the cameras, said Bryan Monell, one of the activists. “He was asking, ‘Have you ever heard of PETA? Are you a member of the Animal Liberation Front? After a while they just let us pass,” Monell said.

Before the group had reached Utah State Highway 21, though, they were pulled over by the Beaver County Sheriff’s Department.

The police officer immediately started talking to them about Utah’s ag-gag law and the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, Monell said.

“He was really adamant about getting hold of our photographs,” Monell said. “He said, ‘There’s a thing called ag-gag out here. I’m not going to say whether I support it or not, but it’s serious. They don’t take kindly to that stuff out here.'”

As officers questioned the group, employees from Circle Four Farms were nearby urging their arrest. “At one point [the employees] started telling the cops that we broke through a barn door and were running through the sheds,” Monell said. “That’s just crazy.”

They were detained for about five hours, they say. Eventually, after repeatedly refusing to turn over their photographs or allow the police to search their cars, they were each given two citations. One for criminal trespass, the other for “agricultural operation interference,” or violating Utah’s ag-gag law.

They were detained for about five hours, they say. Eventually, after repeatedly refusing to turn over their photographs or allow the police to search their cars, they were each given two citations. One for criminal trespass, the other for “agricultural operation interference,” or violating Utah’s ag-gag law.

It’s only the second time that an ag-gag law has been enforced, nationally. The first time was also in Utah. A young woman named Amy Meyer saw a sick cow being pushed by a bulldozer, and she filmed it from the public street. After a news report on this website about her prosecution went viral, prosecutors dropped all charges.

Utah is one of seven states to enact ag-gag laws that make it illegal to photograph factory farms and slaughterhouses. The laws are a direct response to a series of undercover investigations by animal welfare groups exposing horrific animal cruelty.

Right now ag-gag laws are being challenged in court as unconstitutional in Utah. A similar lawsuit in Idaho has the support of 16 different professional journalism organizations along with food safety, whistleblower, and consumer groups.

Right now ag-gag laws are being challenged in court as unconstitutional in Utah. A similar lawsuit in Idaho has the support of 16 different professional journalism organizations along with food safety, whistleblower, and consumer groups.

The activists said that as they were detained, and police officers were talking about felonies and terrorism charges, they had no idea what to expect.

“I really thought I was going to be talking to you from a jail payphone,” Monell said.