David Pellow, a Professor of Sociology at the University of Minnesota, has been outspoken against the government’s attempts to label his student, Scott DeMuth, a terrorist. A few months back he authored a guest post for GreenIsTheNewRed.com, and he has worked with students, professors and the media to raise awareness about how the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act is threatening academic freedom.

David Pellow, a Professor of Sociology at the University of Minnesota, has been outspoken against the government’s attempts to label his student, Scott DeMuth, a terrorist. A few months back he authored a guest post for GreenIsTheNewRed.com, and he has worked with students, professors and the media to raise awareness about how the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act is threatening academic freedom.

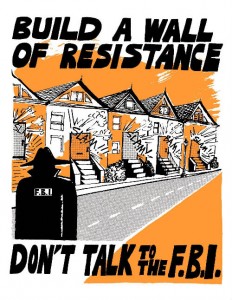

Recently the FBI came knocking at his door. Much to Pellow’s credit, he refused to speak with the FBI agents, and instead contacted his attorney and notified the local activist community.

FBI harassment campaigns are about instilling fear in the activist community, and agents have demonstrated they are not below bringing respected faculty advisors into the witch hunt. Because there have been other FBI visits in the Twin Cities regarding this case, I wanted to share this story.

The following is written by David Naguib Pellow, a Professor of Sociology at the University of Minnesota and faculty advisor of Scott DeMuth:

Scott DeMuth is one of my advisees here at the University of Minnesota. He is a bright, hard working graduate student who has become ensnared in a federal investigation that has left him with the possibility of facing several years in jail related to conspiracy and terrorism charges (his trial begins this summer). The federal government is building a case against him because they believe he has knowledge of at least two Animal Liberation Front actions that occurred in Iowa and Minnesota in 2004 and 2006, respectively.

Scott DeMuth is one of my advisees here at the University of Minnesota. He is a bright, hard working graduate student who has become ensnared in a federal investigation that has left him with the possibility of facing several years in jail related to conspiracy and terrorism charges (his trial begins this summer). The federal government is building a case against him because they believe he has knowledge of at least two Animal Liberation Front actions that occurred in Iowa and Minnesota in 2004 and 2006, respectively.

The U.S. Attorney prosecuting the case has also made it clear that he believes Scott is guilty because he is an anarchist and is believed to be associated with activists who are earth and animal liberation advocates. Scott has indeed worked to educate the public about issues concerning eco-prisoners and other political prisoners in the United States. He has also worked for years advocating for the rights of Dakota peoples, who have been dispossessed of their homelands by military force. And he has done impressive sociological research on these social movements and presented his work at professional conferences. He and I have recently begun collaborating on a research project that focuses on many of these issues. So when the government came knocking on my door I took notice.

Monday April 6, 2010: This morning when I arrived at my place of employment—the University of Minnesota—I went straight to my mailbox. There was the usual pile of academic junk mail—catalogues from publishers, invitations to receptions, etc. But there was something else this time: a business card with a post-it attached to it that read: “re: student, Pellow, 04/06/10, 9:15am.†The business card was for a Steve Molesky, Special Agent, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Minneapolis Division. He also left a voice message for me in my office that stated that he wanted to “interview†me in the next day or so. He didn’t say about what, but the post-it from the receptionist offered an indication (“re: studentâ€).

I immediately called several trusted lawyer colleagues, read the NLG’s “Operation Backfire†guide, and spoke with activists here in the Twin Cities community, all of whom suggested I not talk to the feds. My view on the matter is that I am Scott’s advisor and as such, I should be looking out for him and advocating for him, so talking to people who are trying to build a case against him is probably not in his best interest.

One person also pointed out that given Assistant U.S. Attorney Clifford Cronk’s characterization of me during Scott DeMuth’s arraignment in November 2009 as someone who left him a voice mail message protesting Scott’s detention and criticizing grand juries, it’s likely that they already have formed a certain opinion of me. One of my lawyer colleagues told me that by law I have the right not to talk to the FBI, but if I do then be courteous. My own attorney added that if they persist then I might ask them to send me their questions in written form and that I would run them by counsel.

Wednesday, April 8, 2010: Agent Molesky called my home phone today and left a message that clearly was directed toward asking questions about Scott’s research and my own research. He stated: “I’d like to ask you a couple of questions about one of your students you are the advisor for at the University, Scott DeMuth. I’d like to ask you a couple of questions about the research that you do and the research that he does for you.†I then followed up with a request for a detailed list of questions.

Thursday, April 9, 2010: Agent Molesky replied, “I recognize and understand your request, however, I will probably be unable to satisfy it; not because I don’t want to but because I cannot. I have been asked to interview you by our office in Cedar Rapids, IA. With their request they did not include a specific list of questions. When we conduct interviews, it is more an art than a science, meaning that except for a few questions, I never have scripted questions for an interview–the answers, demeanor, and posture of the interviewee normally dictate the questions I ask and the direction in which the interview moves.†He continued, “I will be asking you about any human research studies that you are conducting in which Scott Demuth may be participating as study personnel. I will also be querying you on your contacts and relationship with Peter Young that may be relevant to the Demuth investigation.â€

After receiving Agent Steven Molesky’s email message today, I spoke with my attorney and we decided that Molesky was firmly within the realm of infringing upon academic freedom. Thus I have decided not to grant the interview request. To speak to Agent Molesky about my research at the level of detail indicated above would very likely violate the American Sociological Association’s Code of Ethics, which states: “Sociologists have an obligation to protect confidential information and not allow information gained in confidence from being used in ways that would unfairly compromise research participants, students, employees, clients, or others.†“Confidential information provided by research participants, students, employees, clients, or others is treated as such by sociologists even if there is no legal protection or privilege to do so.†(Section 11.01). The Code of Ethics also states, “Sociologists do not disclose confidential, personally identifiable information concerning their research participants, other recipients of their service which is obtained during the course of their work.†(Section 11.06).

I appreciate Agent Molesky’s polite and cordial approach to this process, but I cannot and will not violate the trust relationship that I have with my advisee and colleague Scott DeMuth and with the participants in my research study.

-David N. Pellow

Professor of Sociology

University of Minnesota