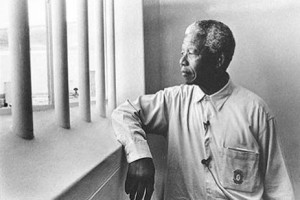

As thousands of people attend Nelson Mandela’s memorial service, and politicians line up to praise him, it’s easy to forget how recently this international hero was viewed as a terrorist and enemy of the state.

As thousands of people attend Nelson Mandela’s memorial service, and politicians line up to praise him, it’s easy to forget how recently this international hero was viewed as a terrorist and enemy of the state.

In Green Is the New Red, I discuss the change. Here’s an excerpt:

Nelson Mandela joined the African National Congress in 1944 to campaign against the South African government’s apartheid policies. As the government’s response grew increasingly violent, and after Mandela stood trial for treason and was acquitted, he argued in 1961 that the African National Congress should set up a military wing. He formed Umkhonto we Sizwe, or Spear of the Nation, and went abroad to study guerrilla warfare and military tactics. In the 1970s and ’80s, the country’s ruling white minority labeled the African National Congress a terrorist organization, and so did the United States. Mandela was later elected president of South Africa. In 1993, he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

President Obama today called him “the last great liberator of the 20th century,” but the United States was one of the most vocal proponents of labeling Mandela a terrorist and placing him on international watch lists.

Many political leaders have now changed their stance. But not all. Dick Cheney is quite blunt in his defense of calling Mandela a terrorist:

Cheney’s staunch resistance to the Anti-Apartheid Act arose as an issue during his future campaigns on the presidential ticket, but the Wyoming Republican has never said he regretted voting the way he did. In fact, in 2000, he maintained that he’d made the right decision.

“The ANC was then viewed as a terrorist organization,” Cheney said on ABC’s “This Week.” “I don’t have any problems at all with the vote I cast 20 years ago.”

Cheney went on to call Mandela a “great man” who had “mellowed” in the decade after his release from prison.

The drastic change in how Mandela is revered today, and how he will be praised posthumously, is a striking example of the fluid nature of the rhetoric of “terrorism.” It’s a term that can easily be modified for the enemy of the hour, and then changed again if those enemies are victorious in their struggles.

The most difficult part of writing the book was dissecting the many definitions of terrorism. But if there is one shared element among all of them, it is this: The term is solely a political one, designed to demonize based on the whims of those in power.

What’s the difference between a “terrorist” and a “freedom fighter”?

Sometimes the answer to that question is quite stark:Â The “terrorist” lost.

If you haven’t read Mandela’s autobiography, A Long Walk to Freedom, it’s excellent.